Glavlit and the organs of cultural regulation in the 1930s

If you were a Soviet writer in the 1930s, there were a lot of people who were extremely interested in what you were doing. These were not just your avid readers, although there were plenty of those around; it must have been a blissful time for authors as the number of literate citizens increased steadily. But before a piece of work could be read by this army of readers, a number of professional organisations took a deep interest in your work including whether it would be published in the first place.

First and foremost the political police in the Soviet Union made strenuous efforts to regulate and control the Soviet literary community throughout the 1930s from the Lubyanka, its headquarters in Moscow.

The political police were not directly in charge of monitoring their creative output as such. But they kept a close eye on literary figures and their works continually updating the Politburo on what they were saying and thinking.

Beyond the walls of the Lubyanka, the work of state censorship was undertaken by a network of arts-related organisations working alongside the political police during the 1930s creating a particular relationship between Soviet intelligence and Soviet intelligentsia. In fact, the Soviet state took advantage of this network to oversee the lives of Soviet writers – gathering intelligence on them and taking the lead in running the extremely complex system of censorship that operated during this time.

These organisations operated in parallel with the political police and some were actually staffed by members of the political police; all of them had the aim of regulating and ultimately suppressing creative works that were not deemed suitable for a Soviet audience.

There seems to be very little that united these organisations of cultural scrutiny. Several of them were large bureaucratic institutions with a great many staff and offices across the vast Soviet territory. However, individuals would also occasionally intervene in matters of censorship ranging from those in the very highest levels of Soviet government – Stalin was frequently involved in the process – down to the writers and editors themselves. The distribution of responsibility so widely throughout Soviet society, both vertically and horizontally, had many implications. Ultimately, with the task of censorship assigned so broadly throughout society, a situation was created in which the task of censoring the output of all Soviet writers became more challenging rather than less so.

The organs of cultural scrutiny

Glavlit

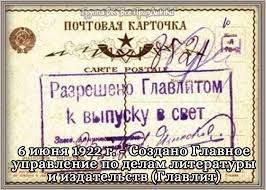

Censorship had been a well established part of life in pre-revolutionary Russia – and immediately after the revolution, became the responsibility of various organisations including Gosizdat (the State Publishing House) and Glavpolitprosvet, Nadezhda Krupskaia’s institution dedicated to fighting illiteracy as well as removing ‘obsolescent literature’ from libraries. There is no question, however, that Glavlit, created in 1922 by the Sovnarkom, Council of People’s Commissars, was the central organ of censorship in the Soviet literary landscape, predating by many years the other organisations that appeared throughout the 1930 affecting the lives of Soviet writers.

It is instructive to note where it sat in the wider scheme of the organs of Soviet government: formally attached to the People’s Commissariat of Education while in practice having regular dealings with the political police, with the GPU given a say in the appointment of its two assistant heads. Glavlit had the legal power to shut down any publishing house that they believed to be engaging in “criminal activity” – and in such cases, it could hand over the investigation of the matter to the local GPU, demonstrating a clear connection between the two institutions. This connection was necessary as Glavlit’s main responsibilities were: ‘… to prevent publication and distribution of works which: contained propaganda against the Soviet regime; divulged military secrets; stirred up public opinion through false information; aroused nationalistic and religious fanaticism; or were pornographic.’[24]

At its inception, Glavlit had just over 300 employees with regional offices from Petrograd to Siberia. By the end of the 1930s, it employed well over 5000 people. Its expansion echoes the growth of the political police: both mutated from being external forces of investigation that operated outside the limits of other Soviet institutions to physically becoming a part of the institutions they regulated. Just as the OGPU stationed their own staff within local machine-tractor station towards the end of the 1920s, so Glavlit installed its own representative (or ‘plenipotentiary’ in the jargon of the day) within each publishing house. This infiltration went a step further in 1931 when a decree from Sovnarkom announced that henceforth all directors of publishing houses would be de facto Glavlit plenipotentiaries.

Moves to unify the process of censorship did not stop with staffing. The Sovnarkom degree required every piece of printed output to carry the date it had been approved for printing by a censor – so that the process of censorship became an ingredient of the finished printed product.

If this suggests an exceptional degree of success on the part of Glavlit in fusing the process of censorship with the other sections of the printing process, two memos commenting on Glavlit’s work makes clear that this was not the case.

The first, produced by Glavlit for the Politburo in 1933, complains of a general deficiency in the quality of staff working in the field of publishing and a failure to integrate with the world of publishing. ‘The editorial staff in our publishing houses are still imperfect and at times even simply weak’, it says. ‘Publishers do not exactly welcome Glavlit, for a censor, of course, causes them quite a few unpleasantnesses of a political and material nature.’ It goes on to describe the practical challenges its employees face: ‘Glavlit’s work is exceptionally intense and operational. We receive the first copies of a print run and within twenty-four hours must have an opinion about the literature we have received today. Otherwise, the book, brochure, poster, or magazine, goes to Kogiz [Cooperative Organisation of State Publishing Houses], stores, kiosks, and subscribers, and then it is very hard to snatch anything back.’[25]

Three years later, the situation had if anything got worse. A second memo on Glavlit’s work, this time for the Orgburo (Organisational Bureau, set up in 1919) details a catalogue of failures on the part of the censors. It begins: ‘An inspection of the work of Glavlit’s central staff shows that the state of censorship in this country is totally unsatisfactory.’[26] The memo goes on to castigate staff for having poor knowledge of the subjects about which they are reading and displaying a ‘careless attitude’. Many staff, far from acting as the guardians of the party, have committed ‘grave political errors’, including exhibiting Trotskyist sympathies, it says – and many have second jobs. Outside Moscow, ‘… in the provinces, and especially in the raions [districts], it is utterly catastrophic. With the exception of Leningrad, Sverdlovsk, Smolensk, Gorky, and Rostov, Glavlit has no real control over what is published.’[27]

A still greater cause for concern was the ‘over-flow pile’ where material that was not reviewed due to shortages of staff and poor training was placed. According to this memo, the amount of material that ended up in the over-flow pile of the political and economic section of the central office of Glavlit was around 70 to 75 per cent. Similar numbers were observed in the agriculture section.[28]

Perhaps as a result of this lengthy criticism, in the summer of 1936 Glavlit sent out a comprehensive set of instructions to all publishers, outlining the process of censorship step by step. It is worth repeating these instructions in full to illustrate the complex process of censorship at this point.

First the plenipotentiary would check the manuscript twice to ensure changes had been made. Then permission was issued to the printer to make precisely 28 copies of the book: with one copy returned to the plenipotentiary, 13 sent to the publishing house and the remaining 14 sent to the local Glavlit office and the Central Committee. When either Glavlit or the Central Committee approve the book, an initial print run was made, with copies sent to the NKVD, the Central Book Chamber and various research libraries. Once these copies had all been delivered the plenipotentiary wrote the words vypusk v svet razreshaetsia (“the distribution is permitted”) on it – the signal that wider distribution of the text could go ahead.[29] I

What’s interesting is while the NKVD did indeed receive copies of all publications, they were a fair way down the food chain in this process of censorship.

Platonov and Literaturnyi Kritik

Andrei Platonov was openly critical of the excesses of Stalinism yet was published by the mainstream journal, Literaturnyi Kritik, throughtout the 1930s. For Future Use, Platonov’s novella chronicling forced collectivisation was published by LK in 1931. In 1936, it published his short story, Immortality this time with a note explaining the difficulties the author had faced when proposing the story to other periodicals. If the criticism of Glavlit had been effective, such continuity would not have been possible.

Glavlit in Ukraine

Kiev was one of many cities brought to the brink of destruction during the Second World War. Employees of Ukrainian Glavlit were evacuated from the city, and almost all of its records for the 1930s were destroyed, with just three slim files from the period 1940-1943 surviving. From these documents, comprising the financial records of Glavlit in Ukraine – including lists of the administrative and censorial roles within the organisation, details of salaries and an indication of the publications for which each censor was responsible – it’s possible to get an idea of how Glavlit operated in Ukraine during the 1930s.

Employees of Ukrainian Glavlit were evacuated from the city and almost all of its records were destroyed – with just three slim files from the period 1940-1943 surviving. From these documents, comprising the financial records of Glavlit in Ukraine – including lists of the administrative and censorial roles within the organisation, details of salaries and an indication of the publications for which each censor was responsible – it’s possible to get an idea of how Glavlit operated in Ukraine during the 1930s.

One document from 1940, detailing the ‘Settlement of Expenses’ for Glavlit Ukraine in that year, notes that funds had to be spent on twenty replacement staff to work as ‘preliminary-control censors’, at a cost of 14,550 rubles [30] – perhaps to replace the original censors who may have been recruited into the army or killed or injured. It also lays out business expenses for trips to Moscow and to the various regional Glavlit offices in Ukraine covering the price of the train fare and accommodation.[31]

Records for the Vinnidkii oblit regional branch of Glavlit Ukrain from 1941 give a sense of the division of labour with administrative staff listed as: the oblit Chief, an accountant, secretary and driver and 44 censorial staff. Each of these 44 staff has up to three of a total of 60 newspaper typed next to his or her name including ‘Collective Farm Worker’ (Kolkhozn. rabota) or ‘Socialist Village’ (Sotsial. selo), as well as the ‘number of outputs’ (Chislo vyxhodov), whether ‘Books-Journals’ or ‘Radio’, that they have censored. Finally, the documents also list the amount to be paid to each member of staff per month.[32] Overall, the impression conveyed is of a large regional office, with a busy cohort of censors all working on multiple titles in various media.

In the documents available for 1943, a picture emerges of an organisation in flux with new staff being taken on and a financial reorganisation led from Moscow being put in place. For example, a letter in the file emblazoned with the letterhead of the ‘Plenipotentiary of the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR for the Security of Military Secrets in the Press and Head of Glavlit’ and bearing an address on Smolensky Bulvar in Moscow, authorises a change in the financial responsibility of Glavlit in Ukraine: ‘The present power of attorney of the main administration for affairs of literature and publishing Glavlit authorizes the Head of the Administration for affairs of literature and publishing for the Ukrainian SSR, com. BARLANITSKY Efim Gregorivich… (1) To be in charge of credit, assigned to Glavlit Ukraine SSR by the state budget. (2) To make all operations open to Gos-bank…’[33]

In another letter from Glavlit in Moscow, confirmation is sent for the hiring of new permanent staff for Glavlit in Ukraine, with 30 to be taken on in October 1943, 45 to be taken on in November that year with a further 52 to be hired in December.[34] in the first quarter of 1944, the Glavlit office in Moscow authorised a further 156 staff, extending this trend of expansion.

These changes in the arrangements for finance and personnel may well have been necessitated by the sheer scale of the devastation wrought on Kiev during the Second World War. However, it is tempting to compare this pattern of change including regular addition of new staff with the patterns of institutional upheaval within the NKVD during the 1930s – and to wonder whether the pattern of administrative turbulence reflected ongoing questions about the poor quality of work done by Glavlit staff so vociferously outlined in the January 1936 memo.

What is clear from one analysis of the Soviet literary process that whatever conclusions we can draw about the workings of Glavlit in the 1930s, the process of censorship was certainly not confined to this one organisation. Indeed it was the Secretariat of the powerful Soviet Writers Union that: … ‘In cooperation with Goskomizdat (the State Committee on Publishing) and the ever-present Party ideological specialists, makes the day-to-day decisions on what works of literature will or will not get published, and in how large a print-run. Manuscripts that do not pass muster have little chance of ever reaching Glavlit, the formal censorship organisation.’[36]

The Union of Writers

‘About two thousand writers were arrested in the years after 1917 and roughly one and a half thousand of them did not survive, meeting their deaths in camps and prisons.’ So wrote Vitaly Shentalinsky, a poet and writer, born in the Soviet Union in 1939 and granted permission during the perestroika period of the 1980s to begin an investigation into the arrest of prominent writers of the Soviet Union. His first step was to write to the Moscow branch of the Writers Union, asking for their help, explaining that: These figures are not complete, of course… Let us try to rescue them!… Only now with democracy and glasnost has this opportunity appeared – if we may believe in real spring and not just another “thaw”. Let us find out if manuscripts burn!”

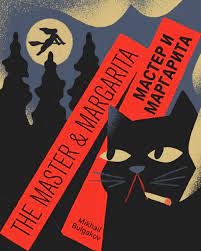

Shentalinsky’s reference to whether manuscripts burn in the last sentence was apposite; the phrase itself came from Bulgakov’s novel ‘The Master and Margarita’, in which Bulgakov parodied the institution of the Union of Writers, attacking what he perceived as its bureaucracy and arrogance.

For example, in the early part of the novel we are introduced to Mikhail Alexandrovich Berlioz, the head of an organisation known as named Massolit, similar to the Union of Writers and its predecessor RAPP (Russian Association of Proletarian Writers). Within a few chapters the unfortunate bureaucrat is dead, run over and beheaded by a Moscow tram.

The response Shentalinsky received from the members of the Union was resoundingly negative and disarmingly blunt: ‘What do you think the Writers Union is? It’s a branch of the KGB. Every second member here is an informer…’[37] What can we make of this extraordinary admission? Was it a de facto arm of the political police throughout the Soviet era and what other methods did it use to control the writing of its members?

Union of Writers: its history

Implicit in the very existence of the Union of Writers is a level of state involvement in the process of writing that is absent in most other nations of the world. Not that the Party ever officially acknowledged any direct connection to the Union itself, as historians Garrard and Garrard explain: ‘The Party does not want to be seen as interfering directly in the literary process, nor does it see itself in this role. It prefers to influence the work of writers through an intermediary: the Union of Writers… But the Party maintains that it did not create the Union; it was created voluntarily by the writers themselves. This myth is necessary to comply with Article 47 of the Soviet constitution, which states that the Union is merely one of several “voluntary societies” which ensure the “freedom of scientific, technical and scientific work”.’[38]

The unionisation of Soviet writers in 1932 was a controversial move by the Soviet leadership both in suggesting that writers, generally solitary and capricious by nature, could be gathered together into a unified group and in risking the impact of the creation of such a body on writers’ work and on the creative process. From the beginning, there were voices of dissent within the Soviet writers’ community.

After his arrest in 1939 and during his interrogation by the NKVD, Isaac Babel admitted to serious doubts about the creation of the union: ‘… I continually attacked the idea that writers be organised into a union, asserting that extreme decentralisation was required in such matters, and that the means used to direct and manage writers should be infinitely more flexible and less apparent… I sharply criticized almost all the measures being taken by the Writers Union and protested against the building of housing, settlements and rest-homes for writers as the beginnings of an anti-professional trend. I refused any posts or voluntary work in the Union and made fun of it…’[39]

After his arrest in 1939 and during his interrogation by the NKVD, Isaac Babel admitted to serious doubts about the creation of the union: ‘… I continually attacked the idea that writers be organised into a union, asserting that extreme decentralisation was required in such matters, and that the means used to direct and manage writers should be infinitely more flexible and less apparent… I sharply criticized almost all the measures being taken by the Writers Union and protested against the building of housing, settlements and rest-homes for writers as the beginnings of an anti-professional trend. I refused any posts or voluntary work in the Union and made fun of it…’[39]

Although groups and associations for writers had existed in the 1920s, the advent of the Union of Writers in the early 1930s was a decisive albeit ambiguous event. On the one hand, it was an institution that was remarkably easy to infiltrate by the political police; that much is clear from the archives.[40] On the other hand, it was an organisation that was set up with the intention of opening up and diversifying the Soviet creative world rather than the opposite. It was one of a number of such organisations set up from the early 1920s onwards, the main one being RAPP, with similar organisations set up in the Soviet republics including the Free Academy of Proletarian Writers in Ukraine (VAPLITE) and an umbrella organisation, the All-Union Association of Proletarian Writers Associations (VOAPP).

As their names suggest, these organisations were exclusively ‘proletarian’ organisations; in other words, non-party members were excluded – a situation that had become untenable by the early 1930s, according to the Central Committee’s resolution on ‘Restructuring literary and arts organisations’ in April 1932. It had concluded that: ‘… the framework of the existing proletarian literary and arts organisations (VOAPP [All-Union Association of Proletarian Writers Associations, RAPP, RAMP [sic], et al) has become too narrow and is slowing the serious sweep of [literary and] artistic creativity. This circumstance is creating the danger that these organisations will transform from being a means of the greatest possible mobilisation of [truly] Soviet writers and artists around the tasks of socialist construction into a means for cultivating exclusive circles for detachment [sometimes] from the political tasks of the modern day and from significant groups of writers and artists who sympathise with socialist construction [and are ready to support it].’[41]

RAPP was an organisation that used explicit dialectical materialism as the basis for their ‘creative method’ – a situation criticised by I.M.Gronsky, a Communist party journalist and member of a five-man commission that oversaw the disbanding of RAPP in April 1932 who was described as ‘Stalin’s right-hand man in literature’[42]. Gronksy recalled a conversation with Stalin in the early 1930s, in which he made his views clear to the General Secretary: ‘… in responding to Stalin, I firstly, came out most decisively against accepting the RAPP creative method, pointing out, in particular, that there were no grounds for mechanically transferring the philosophy of Marxism-Leninism (dialectical materialism) into the sphere of literature and art…’[43] The 1920s are often portrayed as a time of great experimentation in Soviet literature and while this may had some truth, Gronsky’s remarks illustrate the feeling that Soviet literature was already erring towards the ‘mechanical’. In other words, while the formation of the Writers Union has often been seen as a centralising force, it was also seen as the opposite: a loosening of official attitudes to ‘fellow traveller’ writers, and a sloughing off of the formulaic approach to writing adopted by the RAPP dialectical materialists.

A major factor in this positive perception of the Writers Union was that its first secretary was Maxim Gorky, often described as the father of Soviet literature, who returned to the Soviet Union in 1932 after several years abroad to take up this post, seeing a fundamental connection between the role of the Soviet writer and the need for the Union. In 1934, while preparing for the first Writers Union Congress, Gorky wrote to Stalin asking the leader to check through his speech to the congress, and concluding thus: ‘Everything stated above… convinces me of the necessity for the most serious attention to literature – “the bearer of ideas into life” – and, I add, not just ideas but attitudes. Dear, sincerely respected, and beloved comrade, the Writers Union must have very solid ideological leadership.’[44]

However, while it may have had its roots in liberalisation and the patronage of a well-respected author in Gorky, it did not take long for the Writers Union to take on characteristics that had been evident in RAPP and the other writers’ organisations from the 1920s. This was perhaps not surprising, given that many of its new leaders had been involved with RAPP, including Averbakh and Fadeev. Perhaps the main similarity between RAPP and its successor was the setting out of a creative method. In the case of the Writers Union, this method was known as Socialist Realism, a unique and controversial approach to creative work triggering criticisms that the work produced by socialist realist authors is dull,[45] that the Soviet Union they portrayed was rather different from reality[46] – indeed, some scholars even question whether it really is art at all.[47]

The Union of Writers and Socialist Realism

Socialist Realism went hand in hand with the newly formed Writers Union. It was officially launched at the first Writers Congress, held in 1934. In speeches given by both Gorky and Zhdanov, the formula for the new Soviet novel was set out, with Zhdanov making reference to Stalin’s well-known description of writers as the ‘engineers of the human soul’[48]. What is less well known is that Socialist Realism as a concept came into being not as the result of reflections by the Soviet leadership on how to either unshackle the literary intelligentsia or to confine them within an ideological straight-jacket. Instead, it was simply a last-minute fudge, put together in haste and late at night by Ivan Gronsky and Stalin himself.

In Gronsky’s written account of this episode, he explains that Stalin called him on the night before the commission was due to meet to discuss the Writers Congress. According to Gronsky, Stalin asked to see him and questioned him as to whether he had any ideas about a method to replace the dialectical materialist approach favoured by the RAPP writers. Gronsky admitted: ‘I had no suggestions prepared…’ but, like an errant student who has not done the reading for his seminar, he managed to answer the question by diverting conversation to another topic, waxing lyrical on the history of Russian literature for a while, before concluding: ‘These are its special features which in my view should be reflected in the creative method of Soviet literature, a method which I propose to call proletarian socialist, or even better communist realism…’[49] Gronsky – perhaps judiciously – allowed Stalin the final word on the matter. The general secretary expounded: ‘You have found the right way of resolving the issue, but haven’t found a very good formulation for it. What would you think if we were to call the creative method of Soviet literature and art Socialist Realism?…’ Stalin’s formulation would become the template which Soviet writers would employ for the next several decades – as well as the first and most important tool used by the Writers Union to censor writers whose work did not fit this ‘template’.[50]

The titles of some of the key socialist realist novels offer a flavour of their themes of heroism: ‘The Young Guard’ (Fadeev, 1946), ‘The Tanker Derbent’ (Krymov, 1937-1938), and ‘The Life of Klim Samgin’ (Gorky, 1925-1936). However, although certain themes and motifs were present in much of Socialist Realist literature, the publications of this period are not without ambiguity, as Katerina Clark reminds us: ‘… he [the Soviet writer] had room for some play in the ideas these standard features expressed because of the variety of potential meanings for each of the clichés. The system of signs was, simultaneously, the components of a ritual of affirmation and a surrogate for the Aesopian language to which writers resorted in tsarist times when they wanted to outwit censors. Thus, paradoxically, the very rigidity of socialist realism’s formations permitted freer expression that would have been possible (given the watchful eye of the censor) if the novel had been less formulaic.’[51]

The Writers Union had another method of censorship: the rescinding of membership without which a writer was effectively barred from undertaking any work. The poet Demian Bedny was expelled from the Writers Union in the mid-1930s after falling out of favour with Stalin, a disagreement documented in a furiously passionate and intense exchange of letters. Stalin began by offering his blunt criticism of the Bedny’s latest work: ‘Your fable… “Struggle or Die”, in my opinion, is an artistically mediocre critique… Since we (Soviet people) have no shortage of literary rubbish as it is, it is hardly worthwhile to multiply the deposits of this type of literature with another fable…’

Bedny replies: ‘… I have been crossed off at Pravda and also at Izvestia. Things are not going well for me. They are not going to read me after this not just in these two newspapers, everyone has put up their guard. The well-informed Averbakhs have already put up their guard.’ Stalin’s long letter of reply is laced with bitter invective, describing Bedny as petty, proud and conceited. In the closing paragraph, Stalin spits back: ‘Herein lies the essence [in Lenin’s ideas of national pride]. Not in the empty lamentations of the frightened intellectual who rambles on… about how they supposedly want to “isolate” Demian and how Demian “won’t be published anymore” etc. Understood? You asked me for clarity. I hope I’ve given you a clear enough reply.’ It is hard to imagine what it must have been like to receive such a letter from the Soviet leader, but surely Bedny must have been terrified. Although Bedny lost his membership he was not arrested and lived on to try to earn back Stalin’s favour. This leniency would not be shown to other Soviet writers who were ejected from the Writers Union.

The Union of Writers and the purges

- Stavsky not only signed these orders but, further, that he was extremely close to the political police. In a letter to Yezhov written in 1938, Stavsky asks Yezhov to ask for help in dealing with ‘the problems linked to O.Mandelstam’. The letter closes with the ominous phrase: ‘Once again let me request you to help solve the problem of Osip Mandelstam.’[54] Within two months the poet had been arrested, and he would be dead before the year was out.

Writer and broadcaster Olga Berggolts was expelled from the Writers Union in 1937 and arrested by the NKVD in 1938 accused of being a participant in a counter revolutionary conspiracy with Leopold Averbakh, the former head of RAPP who was arrested in April 1937 and executed later that year. Berggolts was arrested by the NKVD in 1937 and in her statement in the file containing the notes on her investigation, she freely admitted to an acquaintance with Averbakh, but denied that she was ever a member of his ‘gang of henchmen’, adding: ‘I was never included and I did not know his plans.’[56] Berggolts paid a high price for her association with Averbakh. The writer was pregnant when she was arrested and after undergoing torture during her interrogation, she gave birth to a stillborn baby. On her release from prison in 1939, she remained loyal to the party, and spent World War Two making radio broadcasts of her poetry to the besieged citizens of Leningrad. In a final twist, she met her NKVD interrogator after the war, who offered her his help saying: ‘Do you recognise me, Olga Fyodorovna? Can I be of assistance?’[57] The NKVD officer was as good as his word and helped Berggolts free her father who was living in exile at that point.

Nikolai Klyuev was another poet whose repression was begun with exclusion from the ranks of the Writers Union: ‘The poet was first… excluded from the Writers Union, hounded in the press, and reduced to poverty and hunger.’[58] Kluyev’s poetry had been a great inspiration to his fellow poets, with Nikolai Gumilyov describing his work as ‘rare and exceptional’. Descended from a family of Old Believers, Kluyev was extremely frank in his criticism of the Soviet Union during his interrogation, condemning collectivisation: ‘I regard collectivization with mystic horror, as a devilish delusion…’. He was equally damning on the subject of industrialisation which he said: ‘… destroys the foundations and beauty of the Russian popular way of life, and is accompanied… by the sufferings and death of millions of people.’[59] In another illustration of the close ties between the NKVD and Writers Union, it was Ivan Gronsky, head of the steering committee of the Writers Union from 1932 to 1933 and editor of Novy Mir between 1932-1937[60], who organised the arrest of Kluyev by making a telephone call to Yagoda, the head of the NKVD. Yakov Agronov, the deputy head of the political police, signed the arrest warrant.[61]

The NKVD files of the writer, Boris Pilnyak, shows how the boundaries between the world of the Writers Union and the NKVD were loose and easily permeated. Pilnyak was a successful and popular writer during the 1920s but his reputation had become tainted around the turn of the decade. Articles about him appeared in the literary and mainstream press with accusatory headlines such as: ‘Boris Pilnyak, Special Correspondent for the White Guard Supporters’ and ‘The Lessons of Pilnyakism’.[62] One article written by the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky has a particularly threatening tone: ‘We must give up subject-less literature-mongering. We must put an end to the irresponsibility of writers. Pilnyak’s guilt is shared by many. Who? That’s a story in itself.’[63]

Pilnyak was arrested and executed in 1938. In 1956, he was rehabilitated, the note in his case file remarking that the pretext for his arrest ‘… is not apparent from the materials in the case file…’ Indeed, the reasons for Pilnyak’s arrest are set out in documents in the case file of his ex-wife, the actress Olga Scherbinovskaya, documents that originate from notes of accusations made at meetings of the Writers Union.[64]

The Writers Union and the political police

The Writers Union was not solely an organisation that could sanction writers by withdrawing membership or prescribe writing methods. It also acted as a conduit for the political police to intervene directly in the lives of the writers themselves. As previously discussed, events such as the first Writers’ Congress in 1934 were a gift to the political police who attended these gathering of writers, producing lengthy reports on writers’ thoughts about the congress itself and the Soviet leadership more generally.

A book produced in the 1980s to mark the 50th anniversary of the Writers Union contains many photographs of that first congress in which the assembled writers look genuinely excited and enthused.[65] Yet reports to the NKVD from the conference – quoting writers who presumably did not suspect that their words would be reported to the political police – vibrate with negative feeling.

Writer Valerian Pravdukhin describes the congress as ‘this servile gathering’, while Aleksei Novikov-Priboy, author of historical novels with a sea-faring theme and winner of the Stalin Prize, gave the following assessment: ‘I sit and listen in pain: according to the speeches and reports, everything’s fine, but for anyone like me, who knows the present literary situation, it’s a real impasse. The period of literature’s total bureaucratisation us upon us…’. Babel expressed doubts about the validity of the Union in the eyes of those living outside the USSR: ‘: We have to demonstrate to the world the unanimity of the Union’s literary forces. But seeing as how all this is being done artificially, under the stick, the congress feels dead, like a tsarist parade, and naturally no one abroad believes this parade.’[66]

It was not just events that the political police managed to infiltrate. The Writers Union was also a provider of homes for writers, a privilege for which many writers were .extremely grateful. Boris Pasternak was delighted at being offered a holiday cottage, or dacha, at Peredelkino, a writers’ retreat, not far from Moscow. Although these dachas were provided by LitFond, another organisation which funded literary activity in the Soviet Union, the money for many of them came from a donation from the Writers Union. [67]

This relationship between writers and housing became further entangled in Ukraine. The House of Writers (Bydynok Slovo, in Ukrainian) in Kharkov, a co-operative block of 68 apartments, built exclusively for writers, was completed in 1929. The first writers to take up residence in the block benefitted from high levels of comfort and even luxury at a time when Party instructions on the building of new dwellings advised builders to ‘economize on materials’.[68] Although the building of the block predates the formation of the Writers Union by a few years, it is very likely that the writers who went to live in Bydynok Slovo were members of one of the fore-runners to the Union, such as the All-Ukrainian Union of Proletarian Writers, an organisation which most writers in Ukraine had joined towards the end of the 1920s.[69] Fascinatingly, the building work on Bydynok Slovo was done by a construction company that had been created under the auspices of the political police, a fact that would later give rise to rumours that the whole building was bugged. [70]

Bydynok Slovo soon became less of a luxurious sanctuary for writers, and more of a gilded cage. In the courtyard of the building, two men, believed to be agents of the political police, became a familiar sight to the residents. Surveillance became a fact of life in the building, and by the end of the 1930s around 90 per cent of the residents had been arrested and exiled or executed.[71]

Although the Writers Union may initially have been set up to be a more inclusive institution than the proletarian writers associations that preceded it, as the 1930s progressed, the Union played a clear role both in the indirect censorship of the work of writers and their direct repression. Writers were spied upon and the Union was used a conduit for this activity. Furthermore, the head of the Union during the time of the purges, Vladimir Stavsky, signed the arrest orders of many writers during the purges during which time: ‘… the Writers Union had seen a virtual orgy of denunciations.’[72]

Two years after the formation of the Writers Union, yet another arts organisation, the Committee on Arts Affairs, came into being, playing an even more central role in the persecution of writers and artists during the purges..

Committee on Arts Affairs

The Committee on Arts Affairs (Komitet po delam isskusstv) was established in December of 1935. The relatively innocuous title of this organisation might suggest that this was simply another layer of bureaucracy. In fact, it was a ‘landmark event in the history of cultural life under Stalin’[73], according to Clark and Dobrenko, evolving in time in time into the USSR Ministry of Culture. The rationale behind the Committee was that since the founding of the Writers Union, other ‘unions’ of the creative industries had been formed, such as the Union of Soviet Composers – and now required an over-arching organisation to unite and guide them. Due to its superior position in the Soviet hierarchy, the Committee on Arts Affairs soon became a more powerful organisation than the Writers Union. It may have had an ideological and policy-setting role rather than having a direct relationship with writers themselves – but that’s not to say that it did not have a great impact on the lives and work of all Soviet artists.

The timing of the setting up of the Committee is important here. Coming into being in early 1936, it arrived on the scene just as the Soviet government was increasing repressive policies against Soviet society as a whole, probably resulting from the murder in late 1934 of Sergei Kirov, a close ally of Stalin and head of the Leningrad Party organisation. Stalin believed that the murder signified the beginning of a campaign to destroy the party leadership and: ‘set in motion an ever-widening cycle of investigations, accusations, trials, and executions that eventually terrorised every institution and touched every corner of Soviet society.’[74] This campaign’s most intense period was in the late 1930s, as Katerina Clark explains: ‘The years 1936-1938… are punctuated by the worst purges, called collectively the Great Purge, that ran from 1937 until 1939, and also by three show trials, one per year: in August 1936 and in January 1937, with the culminating trial of Bukharin and other members of the “right-Trotskyite Block” in March 1938.’[75] The arena of culture was just as much a part of the Great Purge as any other part of Soviet society, she says. ‘In these years there was a tightening up in culture as well, with the secret police playing a greater role.’[76]

Soon after the Committee on Arts Affairs was founded, a ‘marked shift in cultural policy’ took place, comment Clark and Dobrenko.[77] It is unclear whether the Committee itself initiated this shift in cultural policy, whether it was responding to pressure from within the Soviet leadership or whether it was simply mirroring the general trend towards repression within Soviet society at this time. Whichever was the case, this shift had serious implications for Soviet artists with the beginning of what became known as the Campaign against Formalism, an attempt by the Committee on Arts Affairs and the wider Soviet leadership to manage the arrival of modernism in the West. This movement, sometimes known as ‘avant garde’, had swept through painting, literature, music and drama, heralding art that even some in the West found deeply challenging including James Joyce’s Ulysses and Pablo Picasso’s Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon.

In early 1936, Pravda carried an editorial in which the opera by Shostokovich, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, was roundly criticised. The article, headlined ‘Muddle instead of Music’ railed against the composer’s ‘intentionally dissonant, confused stream of noise’, later spelling out the accusation of formalism in rather menacing terms: ‘The ability of good music to captivate the masses has been sacrificed to petty bourgeois, formalist etudes in a vain attempt to achieve originality by means of cheap novelty. This is simply a nonsensical game – a game that can end very badly.’[78] The subtext was clear for any Soviet citizen to see: every facet of Soviet cultural life was now under scrutiny from the highest level. The move against formalism became a campaign of persecution against the Soviet artistic community, spearheaded by Platon Kerzhentsev, head of the Committee on Arts Affairs from its inception, as well as being a member of the Bolshevik Party since 1904, chief of the Agitprop department from 1930 to 1936 and chairman of the Broadcasting Committee.

The website of the present-day Ministry of Culture in Russia devotes little more than a paragraph to Kerzhentsev in its historical review of its past, although it mentions that his policies caused ‘deep resentment’.[79] In fact, Kerzhentsev seems to have been absolutely in tune with the spirit of the times, as is clear from the archives.

Early in 1936, Kerzhentsev wrote to Stalin and Molotov recommending that a play by Bulgakov be removed from the repertoire of the MKhAT (Moscow Art Theatre) as follows: ‘My suggestions: Have the MKhAT annex remove this production not by formal prohibition but through the theatre’s conscious rejection of this production as mistaken and distracting them from the line of Socialist Realism.’[80]

Here we see an intriguing intermingling of many different forces of censorship within Soviet society at that moment – the doctrine of Socialist Realism, the Committee on Arts Affairs in the person of Kerzhentsev, and of course, the ever-present Stalin – all working almost randomly to smother the work of Bulgakov. There may have been processes and policies of censorship in place at Glavlit, backed up by oversight of writers by the Writers Union and other organisations; nevertheless the mechanism used to prevent Bulgakov’s play being staged is the invoking of the policy of Socialist Realism. Furthermore, those making the decisions in this case are not the employees of the organs of cultural regulation, but the head of the Committee on Arts and Affairs and the General Secretary of the Communist Party. This was, perhaps, because Bulgakov was a relatively well-known writer, and therefore matters to do with him necessitated a higher degree of scrutiny than others. Yet even bearing in mind Bulgakov’s status in Soviet society, it is still interesting to note the peculiar manner in which his play was prevented from appearing on the Moscow stage.

Around the same time, Kerzhentsev was writing again to Stalin and Molotov, this time on the subject of the competition for plays and screenplays about the October Revolution. Again we see a fascinating instance of non-Glavlit censorship via the diffuse channels of censorship in Soviet society – as Kerzhentsev, almost casually, suggests circumscribing the subject matter to be used by playwrights and screenwriters for this project. The memo concluded: ‘Please also specify whether to allow the display of other leaders of the party aside from Lenin. I suggest allowing display only of Dzerzhinsky and Sverdlov and assuring a certain interpretation with the dramaturgy and scenarios in connection with further plot refinement.’[81]

Yet another memo to Stalin and Molotov illuminates the relationship between the Politburo and the Committee on Arts Affairs – with Kerzhentsev making the suggestion that all formalist art be removed from the Russia’s galleries:

‘Please consider the following resolution: To accept the suggestion of the Committee on Arts Affairs to withdraw from the general halls of the Tretyakov Gallery and the Russian Museum (in Leningrad) formalist works and those of a roughly naturalistic character of the last 25 years.’[82]

It is unclear whether the Committee on Arts Affairs had a direct relationship with the NKVD in the way that both Glavlit and the Writers Union did. Perhaps by this point in the 1930s, such a relationship was unnecessary due to the very high level of penetration by the NKVD into every level of Soviet society. From 1936 onward, for example, VOKS, the Soviet body entrusted with foreign cultural relations, had to pass all planning for the future directly to the NKVD.[83]

In summary, it seems that the Committee on Arts Affairs was an enormously powerful organisation with a highly political agenda. Although not allied to the NKVD in any apparent way, and with no formal censorship role, the CAA nevertheless had great power over writers including the power to prevent the Soviet public from reading any of their works that were deemed unsuitable.

Stalin the censor

There is one final actor in the process of Soviet censorship in the 1930s: the surprising, and constant, presence of the Soviet leadership in matters related to writing and publishing. As Clark and Dobrenko point out: ‘… censorship had turned into virtually a routine activity for Stalin and the Politburo, one in which virtually every member was involved.’ Correspondence between Stalin and A.B. Khalatov, Chairman of the State Publishing House and Union of State Publishers, on the subject of a forthcoming book of Gorky’s collected works illustrates this situation well.

In early 1930, Khalatov wrote to Stalin saying: ‘I invite you to become familiar with the project of my letter to Com[rade] Gorky on the question of the 22nd volume of his collected works, in which is contained the article on V.I. Lenin, which in my opinion requires serious revision on the side of the author.’[84] Khalatov’s letter to Gorky expresses his doubts about the article on Lenin, highlighting the fact that this volume is aimed at a mass audience, and also worries that comments on Trotsky may be misinterpreted. Interestingly, when Stalin replies to Khalatov about a month later, he is not so concerned about the possible misreading of comments on Trotsky: ‘It will be fine if c[omrade] Gorky agrees with you to make the relevant changes to the article. But if c. Gorky shows doubt or – especially – does not agree with the suggested changes (and he may show doubt as the amendment is a disadvantage for him), you have to publish the article without any changes.’[85]

In this instance, Stalin himself was arguing against the censorship of Gorky’s essay, perhaps putting his own relationship with the author before any ideological concerns. This was not unusual. In their book, Soviet Culture and Power: A History in Documents, Clark and Dobrenko argue that literature and the arts were a serious preoccupation for Stalin.: ‘In this collection we sense the enormous amount of time Stalin – the head of state! – spent reviewing and editing books, film scripts and plays,’ they point out. ‘In terms of the Soviet system Stalin was not “interfering” in requiring changes to these texts but conscientiously fulfilling his role as guardian of the purity of the texts’[86] they add. This reference to ‘purity’ echoes the earlier arguments about the role of censorship in emergent nation – a suggestion that Stalin’s methods of censorship were a positive force, seeking to mould the Soviet state, rather than simply wishing to eliminate all voices of dissent.

Conclusion

While the three most important cultural organisations of the 1930s in the Soviet Union were not necessarily set up to fulfil security or intelligence objectives, they nevertheless ended up working very closely with the political police in a security capacity – both as a conduit for the collection of intelligence, and in the enforcement of censorship.

The role that these cultural organisations played in delivering intelligence to the political police took many forms – from offering opportunities for the political police to gather intelligence at their meetings to deeper intelligence-gathering, for example by enabling access to writers’ homes. It’s clear from the evidence presented here that Michael Herman’s observations on the collection of intelligence taking place outside mainstream intelligence by organisations without a clear security role in the US and UK applies to the USSR. By using information collected by and through cultural organisations gave the political police a greatly increased bank of knowledge about the Soviet writing community. In terms of success, it is clear that this information was used to justify the arrest and subsequent repression of several of the writers mentioned in this chapter – a grim measure of success but one that the political police might well have used. As such, the collaboration between the cultural organisations and the political police was definitely a successful one.

The role that the three organisations played in censoring the work of Soviet writers was varied. Glavlit was the central institution of censorship but both the Writers Union and the Committee on Arts Affairs played decisive roles in what writers were allowed to say and what was not permitted. Glavlit had a clear policy of censorship yet this was not the only channel of censorship – with different tools of censorship involving different organisations and actors could be combined in an almost random way in order to suppress a piece of writing that was not considered acceptable. Patterson’s proposal that censorship is an important element in creating the discourse of a new state helps to explain why the task of censorship was distributed so widely throughout Soviet culture. The continued involvement of Stalin in matters of censorship confirms this.

Whether these multiple organs of censorship were successful is a different question. Despite the multiple organisations acting to censor the work of writers, employing an army of staff, writers were still able to publish works with which the regime disagreed, even at the very height of the purges. Glavlit was criticised on more than one occasion for its defects. And even the combined strength of all of the organs of censorship and the NKVD could not prevent ‘ambiguities’ appearing in published works, nor could they prevent the writing of works of dissent. As Samantha Sherry has observed: ‘… the multiple layers of censorship and the recruitment of editors, translators and writers to act as censorial agents did not, in fact, result in the unconscious and increasingly perfect application of censorial norms, as the totalitarian model would indicate and as the Soviet state hoped. In fact it might be said that requiring agents such as editors to censor works actually opened up censorship to undermining or heterodox influences, owing to the fact that editors brought with them different dispositions, combining their sense of literary responsibility with a clear perception of what the censorship required. As a result of these dual (or multiple) responsibilities, the supposed omniscience of censorship within publishing processes was destabilised.’[87]

It is impossible to understand the relationship between the NKVD and writers without reference to the important role played by these organisations of cultural scrutiny. It seems likely that the NKVD used them to gather intelligence simply because they were there, while in some ways relying on them.

Glavlit, with its clear censorship remit and staffing lvels, was probably the closest to the political police, although the Writers Union was clearly also riddled with NKVD informers. However, Glavlit was the weakest of the three – in a sense almost set up to fail, not least because of the ‘different dispositions’ of its censorial staff.

It remains unclear how these organisations worked together, and, as with so many other institutions at the time seems to have been a little chaotic. In order to understand this relationship, it is necessary to look in greater detail at the cases of a selection of particular writers who were persecuted in the 1930s. In the next chapter, we will begin by looking the case of one of the most famous members of the literary scene in Ukraine, Les Kurbas.

[1] Herman, Intelligence Power in Peace and War, 33.

[2] Clark and Dobrenko, Soviet Culture and Power, p. 140.

[3] See, for example, John Garrard and Carol Garrard, Inside the Soviet Writers’ Union (New York: Free Press, 1990); Herman Ermolaev, Censorship in Soviet literature, 1917-1991 (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1997); Arlen V. Blium, A Self-Administered Poison: The System and Functions of Soviet Censorship (Oxford: European Humanities Research Centre, 2003); Samantha Sherry, Discourses of Regulation and Resistance: Censoring Translation in the Stalin and Khrushchev Era Soviet Union (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015); Andrei Artizov and Oleg V. Naumov, Vlast i khudozhestvennaya: dokumenty TSK RKP (b)-VKP(b), VchK-OGPU-NKVD o kultur’noi politike, 1917-1953 gg (Moskva: Demokratiya, 2002); L. V. Maksimenkov, Bol’shaya Tzenzura: pisateli i zhurnalistii v strane sovetov 1917-1956 (Moskva: MFD, 2005).

[4] Sherry, Discourses of Regulation and Resistance, 54.

[5] Sherry, Discourses of Regulation and Resistance, 171.

[6] Clark and Dobrenko, Soviet Culture and Power, 141-142.

[7] Blium, A Self-Administered Poison.

[8] Samantha Sherry, “Censorship in translation in the Soviet Union in the Stalin and Khrushchev eras,” thesis (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh, 2012), 38.

[9] Sherry, “Censorship in translation,”thesis, 46.

[10] Annabel Patterson, Censorship and Interpretation: The Conditions of Writing and Reading in Early Modern England (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), 3.

[11] Clark, Moscow: The Fourth Rome, 22-23.

[12] Patterson, Censorship and Interpretation, 4.

[13] Clark, Moscow: The Fourth Rome, 94.

[14] Patterson, Censorship and Interpretation, 10-11.

[15] Patterson, Censorship and Interpretation, 21.

[16] Mirra Ginsburg, “Introduction,” in Andrey Platonov, The Foundation Pit (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1994), viii.

[17] Jan Plamper, “Abolishing ambiguity: Soviet censorship practices in the 1930s,” Russian Review 60, no. 4 (2001): 526:544, 526.

[18] Plamper, “Abolishing ambiguity: Soviet censorship practices in the 1930s,” 533.

[19] Plamper, “Abolishing ambiguity: Soviet censorship practices in the 1930s,” 527.

[20] Ermolaev, Censorship in Soviet Literature 1917-1991, 3.

[21] See for example, Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, Nicholas I and Official Nationality in Russia, 1825-1855 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1959), 221-223.

[22] Sherry, Discourses of Regulation and Resistance, 54.

[23] Ermolaev, Censorship in Soviet Literature 1917-1991, 3.

[24] Ermolaev, Censorship in Soviet Literature 1917-1991, 3.

[25] Glavlit’s memorandum to the TsK VKP(b) Politburo on the work and new tasks of the censorship organs. AP RF, f.3, op.34, d.37, ll.25-36. 9 April 1933, quoted in Clark and Dobrenko, Soviet Culture and Power, p. 261.

[26] Memorandum to the Orgburo, “Concerning the Work of Glavlit”, 2 January 1936. RGASPI, f.17, op.114, d.731, ll.72-77, quoted in Lewis H. Seiglebaum, A. K. Sokolov, L. Kosheleva, and Sergei Zhuralev, eds. (abridged edition), Stalinism as a Way of Life: A Narrative in Documents (New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 2004), 148.

[27] Memorandum to the Orgburo, in Seiglebaum, et al., eds. Stalinism as a Way of Life, 150.

[28] Memorandum to the Orgburo, in Seiglebaum, et al., eds. Stalinism as a Way of Life, 148-149.

[29] Ermolaev, Censorship in Soviet Literature 1917-1991, 57.

[30] TsDAVO, f. 4605, Op.1, d. 1, l.56.

[31] TsDAVO, f. 4605, Op.1, d. 1, l.57.

[32] TsDAVO, f. 4605, Op.1, d. 1, l.2-3.

[33] TsDAVO, f. 4605, Op.1, d. 3, l.4.

[34] TsDAVO, f. 4605, Op.1, d. 3, l.7.

[35] TsDAVO, f. 4605, Op.1, d. 3, l.8.

[36] Garrard and Garrard, Inside the Soviet Writers’ Union,5.

- Vitaliaei Shentalinsky, The KGB’s Literary Archive (London: Harvill Press, 1995), 6-7.

[38] Garrard and Garrard, Inside the Soviet Writers’ Union, 8.

[39] Shentalinsky, The KGB’s Literary Archive, 33.

[40] Special Report from GUGB NKVD SSSR Secret Political Department “On the progress of the All-Union Congress of Soviet Writers.” [No later than 31 August 1934]. TsA FSB RF, f.3, op.I, d.56, ll.185-189, quoted in Clark and Dobrenko, Soviet Culture and Power, 168-169.

[41] Resolution of the TsK VKP(b) Politburo “On restructuring literary and arts organisations.: RGASPI, f17, op3, d881, ll6, 22; op163, d938, ll37-38. Original. Typewritten. 23 April 1932, quoted in Clark and Dobrenko, Soviet Culture and Power, 152.

[42] Clark and Dobrenko, Soviet Culture and Power, 162.

[43] Clark and Dobrenko, Soviet Culture and Power, 163.

[44] For more on Gorky and the Writers Union, see Clark, The Soviet Novel, 31-33.

[45] Thomas Lahusen and Evgenij Aleksandrovich Dobrenko, Socialist Realism Without Shores (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 1997), 42.

[46] Katerina Clark, “Socialist Realism in Soviet Literature,” in Neil Cornwell, ed., Reference Guide to Russian Literature (London: Routledge, 1998), 59.

[47] Evgeniy Aleksandrovich Dobrenko and Jesse M. Savage, Political Economy of Socialist Realism (New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 2007), xi-xii.

[48] For Stalin’s full ‘engineer’ quote, see Cynthia A. Ruder, Making History for Stalin: The Story of the Belomor Canal (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1998), 44.

[49] Clark and Dobrenko, Soviet Culture and Power, p. 163.

[50] For more on Socialist Realism in the 1930s, see Regine Robin, Socialist Realism: An Impossible Aesthetic (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992).

[51] Katerina Clark, “Socialist Realism” in Neil Cornwell, ed., The Routledge Companion to Russian Literature, (Abingdon, Oxon: Taylor and Francis, 2002), 182.

- Sheila Fitzpatrick, Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 166.

- Clark and Dobrenko, Soviet Culture and Power, p. 202.

[54] Letter from V. Stalvsky to N. I. Yezhov, 16 March 1938, quoted in Shentalinsky, The KGB’s Literary Archive, 186.

[55] Shentalinsky, The KGB’s Literary Archive, 159.

[56] Protocol no. 14, Session of the Party Committee of the Factory ‘Elektrosila’ named after S. M. Kirov, 29 May 1937, quoted in M. N. Zolotonosov, Okhota na Berggol’ts: Leningrad 1937 (Sankt Peterburg: Mir’, 2015), 73.

[57] Anna Reid, Leningrad: Tragedy of a City Under Siege, 1941-44 (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2012), 414.

[58] Shentalinsky, The KGB’s Literary Archive, 199.

[59] Shentalinsky, The KGB’s Literary Archive, 200.

[60] Yuri Georgievich Felshtinsky, Lenin and His Comrades: The Bolsheviks Take Over Russia 1917-1924 (New York: Enigma Books, 2010), 250.

[61] Shentalinsky, The KGB’s Literary Archive, 198.

[62] Shentalinsky, The KGB’s Literary Archive, 141.

[63] ibid.

[64] Shentalinsky, The KGB’s Literary Archive, 144.

[65] See Georgii Markov, Piat desiatiletiĭ: Soiuz pisateleĭ SSSR, 1934-1984 (Moskva: Sovetskiĭ pisatel’, 1984).

[66] Special Report from GUGB NKVD SSSR Secret Political Department “On the progress of the All-Union Congress of Soviet Writers.” [No later than 31 August 1934]. TsA FSB RF, f.3, op.I, d.56, ll.185-189, quoted in Clark and Dobrenko, Soviet Culture and Power, p. 168.

[67] Olga Bertelsen, “The House of Writers in Ukraine, the 1930s: Conceived, Lived Perceived,” in The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies, number 2302 (Centre for Russian and East European Studies, University Centre for International Studies, University of Pittsburgh, 2013), 14.

[68] Bertelsen, “The House of Writers in Ukraine,” 16.

[69] Bertelsen, “The House of Writers in Ukraine,” 12.

[70] Bertelsen, “The House of Writers in Ukraine,” 16.

[71] Bertelsen, “The House of Writers in Ukraine,” 22.

[72] Clark and Dobrenko, Soviet Culture and Power, 148.

[73] Clark and Dobrenko, Soviet Culture and Power, 146.

[74] Shearer and Khaustov, Stalin and the Lubianka, 170.

[75] Clark, Moscow: The Fourth Rome, 210.

[76] ibid.

[77] Clark and Dobrenko, Soviet Culture and Power, 146.

[78] P. M. Kerzhentsv, “Muddle Instead of Music: Concerning the Opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, Pravda 28 January 1936”, quoted in Kevin M. F. Platt and David Brandenberger, Epic Revisionism: Russian History and Literature as Stalinist Propaganda (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006), 136-137.

[79] “State Administration of cultural development, 1936 – April 1953,” Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation, http://mkrf.ru/ministerstvo/museum/detail.php?ID=273463&, accessed 15 November 2016.

[80] RTsKhIDNI, F. 17, op.163, d. 1099, l.96-99, quoted in Artizov and Haumov, Vlast i khudozhestvennaya, 300.

[81] RTsKhIDNI, F. 17, op.163, d. 1104, l.59, quoted in Artizov and Haumov, Vlast i khudozhestvennaya, 307.

[82] RTsKhIDNI, F. 17, op.163, d. 1108, l.126, quoted in Artizov and Haumov, Vlast i khudozhestvennaya, 307.

[83] Clark, Moscow: The Fourth Rome, 210.

[84] RGASPI, f. 558, Op. 11, d. 822, l. 7. Typewritten script on the form Khalatov. Signature – handwritten, quoted in Maksimenkov, Bol’shaya Tzenzura, 173.

[85] RGASPI, F 558, Op 11, D 822, l 10, typewritten script. Signature – facsimile, quoted in Maksimenkov, Bol’shaya Tzenzura, 183.

[86] Clark and Dobrenko, Soviet Culture and Power, xiv.

[87] Sherry, Discourses of Regulation and Resistance, 176.